by Lee Ordeman When the idea of dissolving the International Shintaido NPO was first proposed, I was strongly against it. For 13 years as a board member of ISC and…

Read moreInternational Shintaido – an evolving organization

by Lee Ordeman When the idea of dissolving the International Shintaido NPO was first proposed, I was strongly against it. For 13 years as a board member of ISC and…

Read more

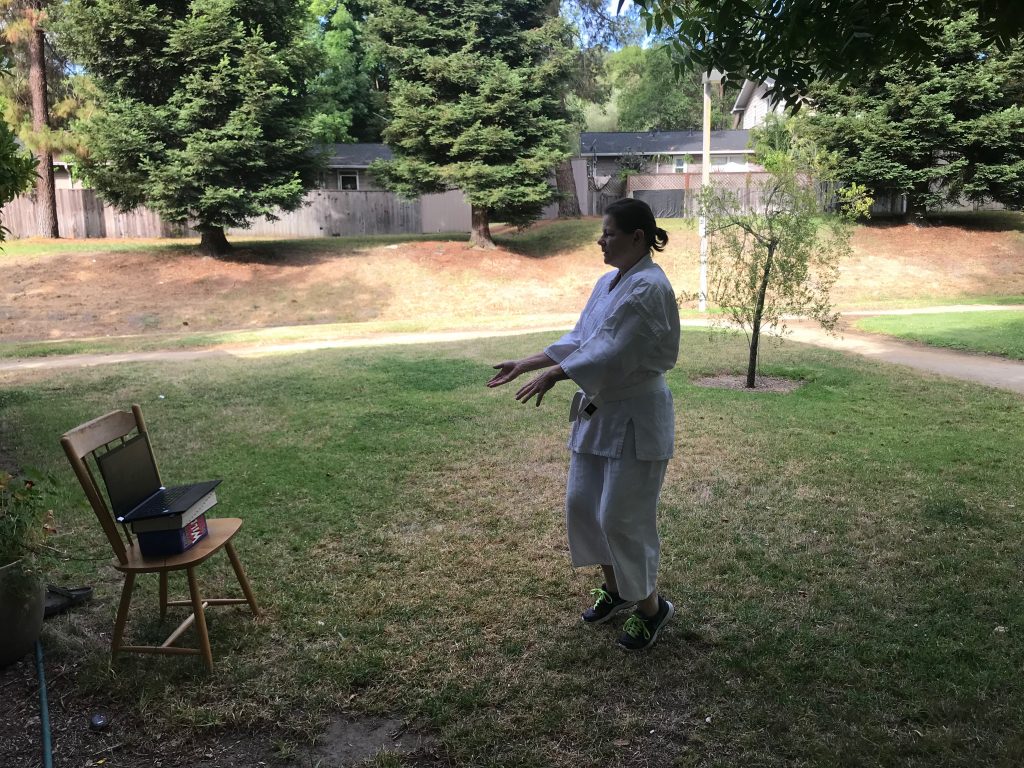

by Connie Borden, Shin Aoki and Derk Richardson New for Shintaido in 2021 was PacShin Kangeiko via Zoom. PacShin offered three keiko on three separate days via Zoom so that…

Read more

Join Shintado of America logo contest!

Read more

This is a publication of British Shintaido. It was the first inaugural lecture, given by Peter Furtado in January 2021, about the Rakuntenkai group who developed Shintaido with Aoki Sensei in the 1960s, and the importance of their mission to the world today.

Read more

As I’m writing this, the Covid-19 virus is spreading rapidly in many parts of the world and there are a lot of restrictions on various kinds of public gatherings and…

Read more

By Derk Richardson

Henry Kaiser took up the guitar in 1971. The next year he traveled to Japan for the first time. In 1977, he visited Japan again, and among those he met was avant-garde trumpeter Toshinori Kondo, who was also a Shintaido practitioner*.

Upon his return to the San Francisco Bay Area (he was born and raised in Oakland), Henry immersed himself in Shintaido practice under the tutelage of H.F. Ito and attended classes in Berkeley, CA. taught by Bela Breslau.

Subsequently, over many years, Henry played guitar at Shintaido events. Outside of Shintaido, in addition to live performances all over the world, Henry has recorded hundreds of LPs and CDs. Even those previously unfamiliar with his music should be able to discern certain parallels with Shintaido—the dissolution of ego; the inseparability of form and expression; the wakame-like flow (Henry has also been a scuba diver for nearly 50 years); the improvised responsiveness in spontaneous collaborations, i.e. musical kumite.

In this video, number 20 in the series of weekly guitar solo videos he has been recording for the Cuneiform Records YouTube channel since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Henry talks about his musical relationship with Shintaido and shares his “Shintaido guitar” performance video from 1990 in London.

*Mr. Kondo passed away in October of 2020.

By Connie Borden & Robert Friedman of Fearless Branding

Have you found yourself struggling to explain Shintaido? Wondering how to express yourself to others so that they might come to a class? Well you are not alone.

The SOA board and SOA NTC members had the same discussion in December 2019 and again in March 2020. Most of us could think of similar discussions over the years since we began to study Shintaido. Perhaps even too many discussions without a tangible result.

It is almost 45 years since the organization of SOA was co -founded by Ito Sensei and Michael Thompson Sensei. Many members have 30 plus years of study and have assumed leadership roles in teaching and organizational matters.

So, as we asked ourselves, “When is the right time to explore branding with a consultant?”; the answer was now is the right time. Why should we wait?

We asked ourselves, can we clearly express in English our value of the practice of Shintaido? Can we express our love of Shintaido so that other’s will be interested to try a class?

With this desire to define the essence of Shintaido’s value and our wish to expand and attract new members to preserve and grow Shintaido, we hired Robert Friedman of Fearless Branding.

What is the purpose of a brand? By answering five fundamental questions, we defined WHAT to say. We developed two types of messages: New content for the SOA Website and messages for our instructors and members to explain Shintaido to people who want to learn more.

Robert Friedeman shared his thoughts about branding and Shintaido.

The most important job of branding is to tell your people who you are. The way I do branding is to help the stewards of the brand answer five questions:

– Who are you?

– What do you do?

– Who do you do it for?

– What do they need (and want)?

– What do they get?

I wanted to work with SOA because my husband, Shin Aoki, is a long-time member. He has devoted much of his life to practicing and teaching Shintaido and to the Shintaido community. Many people in the community have been friends and practice partners for 30 years or more. Shin’s dad, Hiroyuki Aoki, created Shintaido. So, it’s kind of like the family business. Except it’s not a business ☺.

One thing I have noticed is that Shintaido practitioners are so loyal. Once someone is hooked, they never stop. Many of Shin’s friends and students have been doing Shintaido for 10, 20, 30 years, or even longer. BUT, Shintaido does not attract many new students. Why is this? There are two simple answers: 1) long time practitioners, and especially teachers, felt they didn’t have a clear, easy way to explain Shintaido. 2) There is very little marketing being done. A big part of why there is very little marketing being done is that Shintaido teachers are not marketers and they don’t have good tools to use to help them tell their story and articulate the value of Shintaido. If Shintaido could create simple and effective tools, it will make it much easier for teachers and other SOA members to do some basic marketing – which is to find people who might be interested and tell them about Shintaido in an interesting, non-pushy way. I felt my talents could help Shintaido make significant forward movement to be better marketers and attract the new students that would love Shintaido and reap its benefits.

With Robert’s guidance, four people volunteered to commit to work for three months. We met weekly for 1.5 hours and completed weekly ‘homework’ assignments. In our facilitated meetings, we distilled our answers to the essential core values. We discussed, reviewed, and discussed again. True consensus was reached through the facilitated meetings. Our group reflected diversity in gender, age, native language, and geography.

The Committee members were:

Connie Borden, SOA President and SOA NTC member

Lee Seaman, SOA NTC member

David Franklin, SOA Board member and SOA NTC member

Herve Hofstetter, SOA Board member

Check out this video where the members speak about their experience with the project.

As a result of our work we discovered the following theme and what it entails.

Shintaido – Opening to Life

We believe that when we open our bodies, we open to life.

When we open our bodies, we can receive and connect with others. But it also makes us vulnerable.

When we use cutting movements our intention is not to defeat our opponent, but to help the people we practice with to cut what no longer serves. A primary purpose of Shintaido is to build a diverse community and to create community with others. We cannot do it one our own. In Shintaido, you help me grow.

Shintaido classes, called keiko, include solo work, group practice and partner exercises. We use voice as well as our body.

We are working on new content for our SOA home page. Robert Kedoin in collaboration with Robert Friedman is developing the new page

Also, we are considering creating a new logo. If we decide to move forward, we will ask for your feedback. Let’s use our creative talents!

The process of implementing our Shintaido Brand – Opening to Life will be ongoing. Please try some of the messages. Do they inspire others to try a class? Please share your feedback.

We are a community of seekers. I hope this article may give you a chance to look deeper into your practice of Shintaido.

By Jim Sterling

After many hours of filming and editing we are happy to provide a series of 12 videos that show some of the movements practiced during Pacific Shintaido Kangeiko and the National Technical Committee’s Advanced Workshop in January 2020. Many thanks to Mike Sheets who shot over 20 hours of videos and Sarah Baker who contributed her extensive editing expertise.

Here is a link to the videos on the SOA YouTube channel

The videos speak for themselves but briefly they include footage from Kangeiko showing various arrangements of Kyukajo and Tenshingoso. Also, there is an in-depth review of Taimyo and Flower walking among other familiar movements.

The Advanced Workshop concentrated on Jissen Kumitachi and features Chudan no Kata and Okuden no Kata. These are the only widely available videos of these two-high level kata and are important aspects of our Shintaido Kenjutsu program. Wonderful examples for review and study purposes. Don’t miss the naked blade version of Diamond Eight Kata !

For a detailed description of the Kangeiko curriculum, please read Derk Richardson’s beautifully written article from SOA’s Body Dialogue archives.

“Rediscovering Kyukajo: Pacific Shintaido Kangeiko 2020”

Many thanks Ito Sensei and all the students who were willing to give their time and energy during the taping.

These are the first of many videos to be released on our new and improved SOA YouTube channel. Stay tuned for more in 2020 – 2021.

By Sandra Bengtsson

Listening to a program on the radio about a vaccine for Covid 19, I heard the following statement: “We can’t use the outdated techniques of January 2020 to develop this vaccine”. January, 2020, outdated – really! But if we look at life now compared to then it’s an understatement.

The last Shintaido class I attended in person was on March 8th at our usual Sunday at Marin Academy, just north of San Francisco. This was our regular weekly class that Robert Gaston, Connie Borden and I have co-taught for several years. Curriculum varies, but we had been focusing on Shintaido Kenjutsu and Jissen-Kumitachi. Per usual, after keiko we went to eat, and amid the bustle of brunch talked about the virus and what we knew. Connie, as a medical professional, gave us an update on viruses in general and we all discussed our thoughts, feelings, and concerns.

On March 16th, the Bay Area was placed under a Shelter in Place order. My husband and daughter Rob & Sally Gaston and I shared our very cozy home for the next 10 weeks, leaving only to buy groceries or take walks.

Rob had been participating in Pierre’s Taimyo remote keiko but since that was in the middle of my office workday, I hadn’t. At home I could and I did. It was a lifesaver. While I was never drawn to Taimyo – this approach, in this time, was perfect. A little before 2pm an alarm would go off on Rob’s phone – it was like a call to prayer. I set aside my work and settled myself into Taimyo.

We began teaching Sunday class on April 5th via Zoom. Keiko is 45 minutes: Warm-ups, Kata (Taimyo/Tensho/Diamond Eight) and a brief conversation afterwards. It’s been a comfortable time to re-connect, practice familiar movements and keep our weekly Shintaido schedule active.

Around May 1st, Connie mentioned to me that there was going to be a British Shintaido Online Daienshu June 7th-21st. The format was Sunday keiko with Minagawa and Gianni, during the week personal Taimyo kata and several keiko in small groups, each led by an instructor. As my first international event was a British Shintaido Daienshu in 1989, I thought why not?

As I do prior to every event, I began my plan to reduce my involvement in the gasshuku. I had limited expectations about Zoom keiko; the keiko times were earlier than advertised; I couldn’t practice during the week because I was back to work—all variations on my usual pre-gasshuku angst. In fact, I said to Jim Sterling prior to this event, “if Gianni teaches stepping, I’m going to ask for a refund!”

The first Sunday keiko came and it was really something. Minagawa & Gianni taught as they always had: warm-ups, tachi jumps, eiko dai, tenso, shoko, daijodan kirioroshi, taikimai and azora taiso, finishing with self-care. Some movement was open hand, some with bokuto.

They weren’t teaching as they always had, but what was happening was gasshuku keiko. The teaching method was familiar: sensei demonstrate, sensei and students perform the movement one time together, and then students practice individually while sensei encouraged, corrected and supported.

Afterwards was the discussion: heart-felt, a bit too long, with extensive “thank yous” and clapping. A real post- gasshuku discussion!

Next came Sunday 6/14. Again, many of the elements of the first keiko, progressing to stepping practice and then to expansive movement. And no, I didn’t want a refund. It was amazing! In a very small space Gianni taught hangetsu stepping practice, tenshingoso dai, tsuki to many levels, leading to tsuki moving freely. In my small living room, I was transported.

And for the last keiko, Minagawa began the keiko with Diamond Eight movement. Then as Gianni taught the balance of the class, he presented (a new to me) sword kihon using portions Diamond Eight movements. I was so excited to be offered new movements to practice and learn!

After class, we had a final discussion, complete with a group photo – “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

To assess these approaches, I look at both the teacher and student perspectives. Most importantly from the Daienshu, it was extremely successful because the sensei did not limit themselves when presenting the classes through Zoom. This was critical. As a student, I had a more positive and enriching experience when I concentrated on receiving the teaching as it was presented, and did not focus on how it was different from gorei I had received before. In both cases, the Zoom filter was removed. Just when I forgot about “Beginner’s Mind” it came to the forefront again.

My thoughts on these approaches to keiko:

Taimyo

Practicing a specific movement at a specific time with others across the world reminded me of the power of Shintaido. We know how to move through space and time; this ability enhanced this practice. I could feel others practicing and they felt the same. Pierre’s gorei directed me and connected me to Taimyo.

Narrative gorei: Students listen and move as verbally instructed by sensei: “reach to front as in “E” then when reaching eye level , open to “O” and then exhaling circle back low then front softly, “O” not too high”

Sunday class

Visual and audio gorei: Students watch and follow, with verbal & physical presentation of the movement by sensei.

SGB Daienshu

Again, what really worked about the Daienshu was that the teachers did not allow themselves to be limited by Zoom. Neither Minagawa or Gianni referred to it except for minor technical reasons. It allowed us to connect, but did not limit the connection. Also, was clear that a great amount of time and thought was spent creating a cohesive, expansive and integrated program.

As we continue with virtual keiko we will develop and fine-tune these styles. I have gone from being pretty down-hearted to quite enthusiastic about the possibilities. Gorei as a thread that lifts and carries us is being re-defined.

Aoki-sensei quotes from the code of Master Koizumi on page 61 of the Shintaido text book:

“Martial arts must change with the demands of each age, otherwise they are of no use to the warrior.”

YouTube Link – Sunday Zoom Keiko with Sandra, Rob Gaston and Connie Borden