As I’m writing this, the Covid-19 virus is spreading rapidly in many parts of the world and there are a lot of restrictions on various kinds of public gatherings and meetings. There are limits on the number of people who can gather, even for outdoor exercise. Of course, this means people are spending a lot more time at home or alone. Here in the Czech Republic, there was a two-week ban on singing in music classes in elementary schools, high schools, and music conservatories, because using your voice — singing or yelling — can spread the virus.

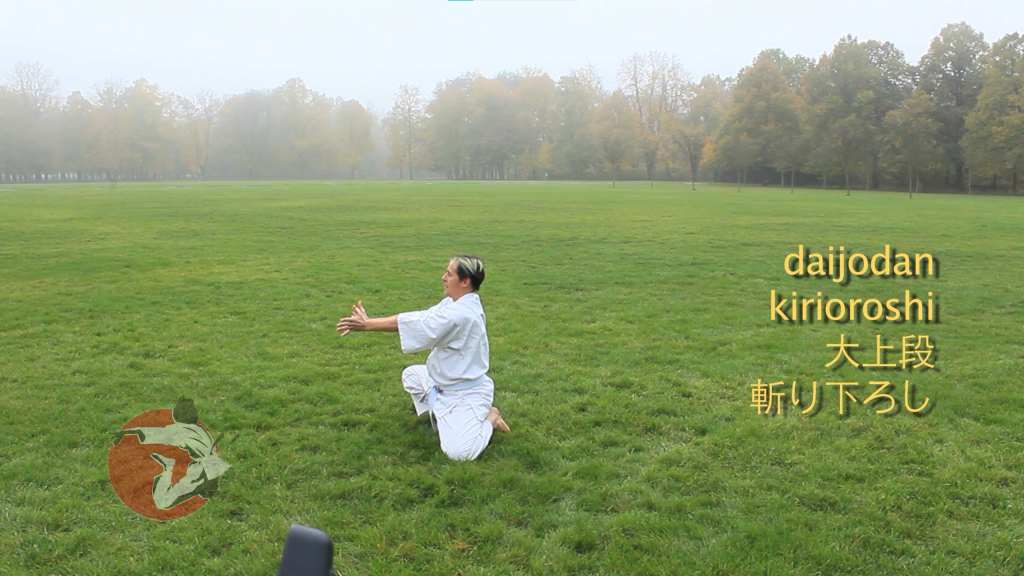

Considering that using an expansive voice is a component of two of the three fundamental techniques in Shintaido, and also feeling that this whole situation is making many people want to scream at the top of their lungs, I decided this would be a good time to encourage people to practice Eiko Dai — the signature Shintaido technique in which one runs far and yells loudly — safely. So, I made a video about doing Eiko outdoors alone, and also about how to do the miniaturized “bonsai” versions, Daijodan kirioroshi and Daijodan kirikomi musubidachi.

Also, the video includes an example of doing Eiko with the bokutoh, the unique type of wooden sword used in Shintaido. I show demonstrate how to grip the bokutoh properly and glance at the different shapes of the traditional katana (metal sword), the traditional bokken (wooden sword), and the unique Shintaido-style bokutoh.

A few years ago, I completed a master’s degree at Université Paris 8 St-Denis, where Pierre Quettier, a long-time Shintaido instructor, became my thesis advisor. The theme of my thesis was about types of knowledge that are usually only communicated face-to-face. What types of things can you only learn when you are physically in the same room with the teacher? What are the things that normally cannot be recorded by a video camera, and why?

These questions were incorporated into the process of making the video. One of the tricks I used, was that while making the video, I was also live-streaming the practice and had a few people participating. I had my phone (for the Internet streaming) and a video camera recording at the same time. Psychologically, this put me into a more familiar mental space. Rather than performing for the camera, I had to teach the class “in real time” for the people who were participating remotely. This made me speak and present the techniques in a more natural way, while still trying to be aware of the fact that I was communicating through the medium of the camera and the Internet.

But rather than posting the recording of the whole practice unedited, I then went to the studio and the editing console and made a more finished product. I added a few close-ups and different camera angles of technical details that I couldn’t shoot out in the field. I also “opened the curtain” and revealed myself in the role of video editor. Instead of the video editing process being a kind of hidden “magic,” I wanted to increase the audience’s awareness that the video they are watching has been crafted and designed to present the information to them in the best way possible.

Finally, I added subtitles — in English. Why would I add subtitles in English, when I’m speaking English in the video? I believe this could increase the online “reach” of the video. It’s called the “world wide web” because it is in fact world-wide, and that means it’s possible that people in many countries may see the video. My experience as an English teacher in the Czech Republic has shown me that many people can read English better than they can understand spoken English, and often people studying English enjoy watching videos in English with English subtitles so that they can learn pronunciation and improve their ability to understand spoken English. It’s a way to improve access for people who are not native English speakers, without actually translating the subtitles into a foreign language.

My hope is that people will not just enjoy the video, but that it will inspire them to get up early in the morning when there are not many people around and go out to a place where they can safely use their voices to the fullest extent. In my opinion, shouting at the sky is incredibly beneficial to both the body and the psyche, and it’s worth the effort.

Here’s the video:

* Written, performed, shot, and edited by David Franklin. Featured book: “Shintaido: The Body is a Message of the Universe” by Hiroyuki Aoki, English trans. by H.F. Ito and Michael Thompson. Music: “Future Gladiator” by Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com), licensed under Creative Commons: by attribution 3.0 http://creastivecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Bravo David. Very clear, very informative and very useful

Wow! A very rich, concentrated 10 minutes of instruction. I liked the subtitles and diagrams.