by Jim Sterling On February 5, 2021, Shintaido of America (SOA) held a celebration via Zoom to honor Michael Thompson, Doshu, with a Lifetime Achievement Award. During this event over…

Read moreMaya Meets Shintaido

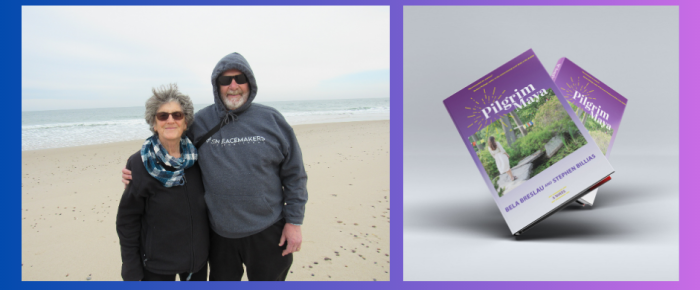

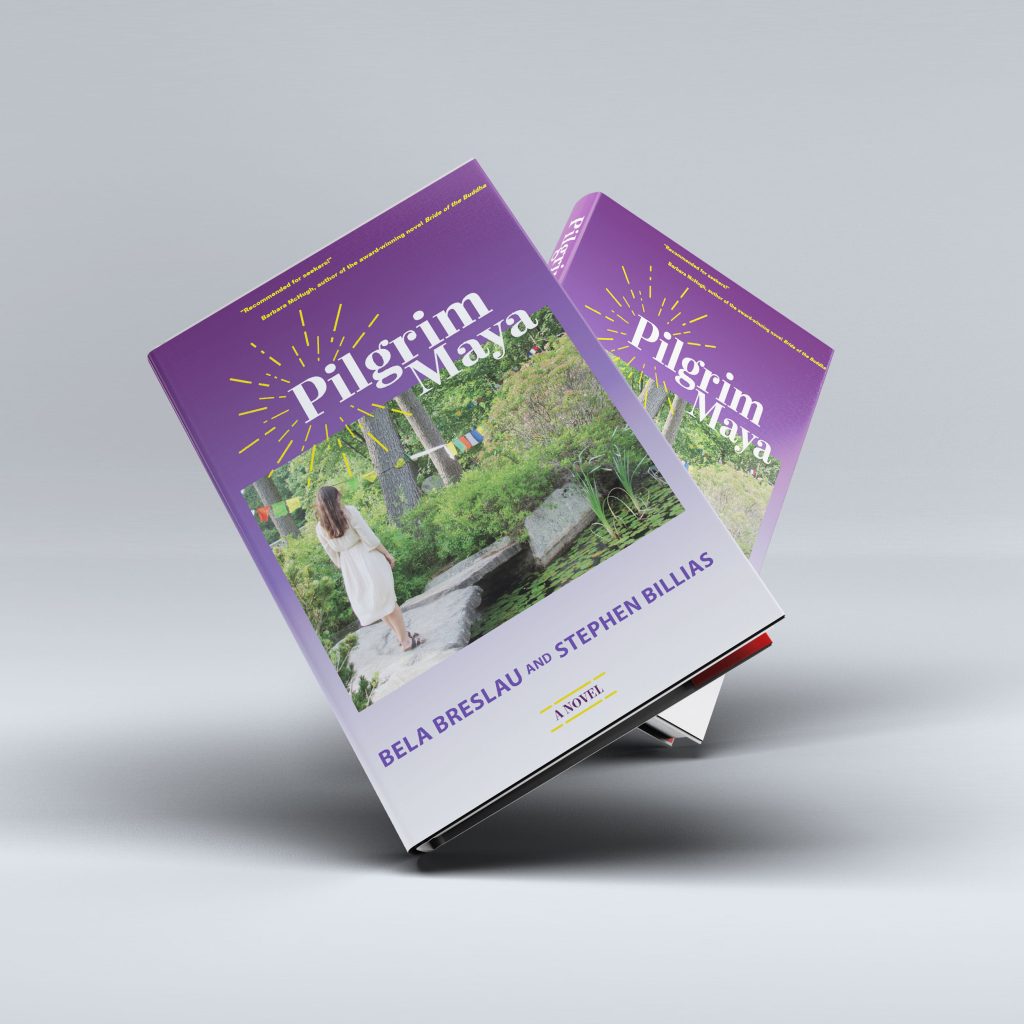

by Stephen Billias

General Instructor Jim Sterling asked me and Bela to submit an article to Shintaido of America’s Body Dialogue newsletter, using excerpts from our recently published novel Pilgrim Maya that reflect our background as longtime Shintaido practitioners.

Although we never use the word Shintaido in the book, Shintaido was the inspiration for many scenes. We have both put many episodes from our lives into this novel. For example, in one chapter the main character goes to Japan and attends a wedding. Bela participated in a wedding ceremony in Japan. In this article, though, we’re going to confine the excerpts to two that will be familiar to anyone who has practiced Shintaido, especially those practitioners in the Bay Area.

In Pilgrim Maya, the main character, Maya Marinovich has lost her husband and baby daughter in a freak car crash. To find a new start, Maya leaves Boston for San Francisco. She gets involved briefly, but passionately, with the leader of a Japanese-Jewish cult movement. This part of the novel is not based on Shintaido, but the excerpt below about a hike up a hill in Tennessee Valley in Marin County will be familiar to Bay Area practitioners of Shintaido. Ito-sensei led many groups up that hill over the years. In the second third of the novel, Maya, lands a job as assistant property manager for The Bon Vivants, a group of artists in a co-housing building in Oakland. Later she learns details about the accident and spirals into depression and thoughts of suicide. In the final chapters, Maya meets Buddhist teachers Eli Ronen and his wife Reva, and begins a lifelong process of healing and transformation, finding meaning through helping others. Here are two excerpts that were inspired by our Shintaido experiences.

A hike in Tennessee Valley:

Chapter 8 The View from the Top of the World

It’s not that easy, I discover, to get to Tennessee Valley without a car. I suppose I could have asked one of the Tribers, but I’m still clinging to a loner’s independence. I take two buses and a long walk to get to the trailhead, at the upper end of a deep valley that leads to an ocean beach. The vivid air smells of sage and salt. It’s easy to find the Tribe of Dan in the area in front of the parking lot by the first gate into the valley, a common meeting point. Their white robes make them stand out from the young couples with baby strollers and the avid hikers in shorts and hiking boots. When I arrive, a California Highway Patrol officer is interrogating Sajiro while the rest of the Tribe stand around looking amused. Manami comes up to me immediately.

“Wonderful,” she says. “Glad you came.”

“What’s going on?” I ask.

“Oh, we get this all the time. He just wants to make sure we’re not a terrorist group.”

“Are you a terrorist group?” I ask. Manami just laughs. The CHP officer soon leaves, apparently satisfied that Sajiro and his people aren’t going to blow up anything or throw themselves off a cliff in a mass suicide. The Tribe starts down the flat, easy trail out to the beach, but after a quarter mile they veer onto a steep path up the side of the hill. I struggle to keep up. Sajiro is a good hundred yards ahead already. I can’t tell whether his followers are letting him be ahead or whether he’s just in much better shape than everyone else. It takes us a good forty-five minutes to crest the ridge. We walk another quarter mile to where the views are most spectacular up and down the coast and far out to sea. I wonder if we’re going to do more chanting and moving, but we don’t. All we do is face the ocean in a natural stance. Though he isn’t saying or doing anything, Sajiro is leading us. Some people have their eyes closed. Others have them open. I’m looking around, wondering when we will finish, wondering what this is all about and at the same time totally enjoying being here on the continent’s edge with amazing views of the Pacific.

After the meditation, Sajiro turns and stands with his back to the ocean, facing us. “This is always here,” he says, gesturing to the panorama of sparkling water, golden hills, a cloudless day with a heaven full of different shades of blue, sky and ocean meeting at a soft line in the far distance. “Don’t be afraid to come back here, any time. Even if just in your mind.” The walk down is somewhat easier. I catch a glimpse of the city of San Francisco, just for a minute between the hills. It shines white and pink like a fairy castle in the air. Then Sajiro is walking by my side.

“Very beautiful and peaceful, isn’t it?” he says.

I nod, still somehow embarrassed and strained by being near him. He laughs easily and puts his arm over my shoulder and says how glad he is that I have decided to be open to the beauty around me, and that it reflects the beauty that is inside me. I am surprised at the ease and innocence of his gesture and what he says. I laugh easily also, letting go of the tension and uncertainty.

A keiko in a Japanese martial art that strongly resembles Shintaido, followed by an episode of takigyo (waterfall training) that some Shintaido practitioners (including Bela) have experienced:

Chapter 21 Zen Body, Zen Mind

The next time I do yoga, I see Jimmy again and am impressed by his physical agility, grace, and balance. I remember what he said about studying a martial art of some sort. Over the next several weeks, I start looking into martial arts. As helpful as I find yoga, the nightmares have persisted. Maybe something more active and rigorous would speed things up, dislodge the body memories of nighttime car crashes. Something tells me it might also augment my development in meditation. I’m never sure what drives me but with the help of my Zen teachers and my therapist Sarah, I’m coming to trust and believe in myself and I follow my intuition, my instincts. It’s San Francisco—with a cornucopia of offerings available—tai chi, karate, aikido, tae kwon do, as well as lesser-known practices. I try classes in different forms but nothing fits. Tai chi is too passive, karate too focused on combat and self-defense. I continue my long walks, and on a sunny Sunday afternoon, I find myself in front of the Kiri-Do dojo on California Street. With a start I remember that this is the family dojo of my new friend from yoga, Jimmy. A large poster covers the window.

Need to Change Your Life?

Try Kiri-Do (The Way of Cutting)

The Martial Art for Personal Transformation

A jolt runs through me as I read the words. That’s me: I need to change my life. I’m on the path already. Maybe Kiri-Do is what Sarah was getting at when she suggested a body-centered practice. At the end of the next yoga class, I approach Jimmy and ask about beginners’ classes.

“We’re all beginners. We always will be. You should just come. We all practice together. Are you free Wednesday night? If you are, come by. I’ll be there too.”

So here I am showing up for class on a drizzly San Francisco Wednesday night. I’m wearing grey sweatpants and a long-sleeved white t-shirt. The dojo is a nearly empty room with a scuffed and worn wooden floor and a tokonoma altar in one corner. Everyone leaves their shoes and street clothes in the outer entry way. The first thing I notice is that there are few students, and they’re all in incredible shape. A youngish woman welcomes me. She’s not Japanese, but she’s dressed in a white martial arts outfit I later learn is called a gi.

I’m surprised when Jimmy comes out. He’s wearing a white uniform, white special shoes, and a white skirt-like covering that makes him loom large. When he sees me, he smiles broadly and nods in my direction. The class is about to start. Jimmy has everyone form a circle.

Jimmy leads warmups, a series of increasingly strenuous stretches, starting at the top of the head and working down to the lower part of the body. It’s not too hard. I’m getting a bit comfortable. We reform the circle at the end of warm-ups and have a short standing meditation. An older Japanese man walks out from a back room. He’s shorter than Jimmy, and has the square body of a martial artist, compact, muscular, with short-cropped gray hair and glasses. His face is severe, with none of the easy warmth Jimmy projects. He notices me right away and comes over to me while the rest of the class waits on the side. Jimmy hurries over to make an introduction.

“Father, this is Maya, a friend of mine from yoga class. Maya, this is my father, Mr. Ueda. In class we call him Sensei.”

Sensei nods. “Hello, Sensei,” I say, and I bow, something I learned from my time in the Tribe.

“Please just follow. You are not expected to know what to do. Jimmy will be near you.”

What happens next surprises me. There are a series of partner exercises that include leading and following and jumping. Lots of jumping. After twenty or thirty minutes, I am completely exhausted and surprised. I thought I was already in pretty strong shape, but these exercises are something else. Also, there is something to the way we are touching one another. Holding out our hands to support the person doing the jumping. Jimmy comes by to be my partner toward the end of the break-out session and I follow as best I can. When I lead him, I notice how the slightest movement on my part sends him jumping up almost to the ceiling. I try to pull back my energy, but he just smiles at me and continues.

We again stand in a circle for a brief calming meditation. We do some strange movements accompanied by sounds. I continue to do my best to follow. The rest of the class is more technical. As far as I can tell, it’s basic karate stuff, except the students aren’t sparring, there’s no headgear or padding, and when they do partner practice, they don’t strike each other. I try to follow Jimmy’s father, the teacher, but it’s hopeless. He doesn’t explain anything and pays no attention to me. I’m supposed to copy what he’s doing, without any instruction. Oh well, I think, waiting for the class to be over so that I can leave and never come back. A funny thing happens toward the end of class. We take up wooden practice swords. I notice that each of the students has one of their own, carefully wrapped in cloth scabbards or furoshikis. Jimmy gives me a loaner. We follow Sensei in a series of cuts. Jimmy comes over to correct my form because I’m holding the sword upside down, but in my defense it’s hard to tell, since the thing, I learn, is called a bohkutoh and is just a straight, heavy piece of hard wood that barely resembles a sword; it has no curve and only the hint of a blade edge, though it does have a rough point which keeps me from holding it by the wrong end, thank goodness! The funny thing is, I like it all—the sword, the cutting, everything!

After the class, Jimmy comes over to ask how I am and what I thought. The other students are filtering out of the dojo, bowing to the Sensei and bowing at the entrance before turning to leave. I intuitively understand that they are appreciating and acknowledging the sacredness of their practice space. My time with the Tribe and in Japan taught me at least that much.

Just as I am about to leave, Jimmy’s father comes over to the two of us.

“Why are you here?” he asks. It’s a challenge. I wonder: Did I do something wrong. Have I presumed too much in some way I’m unaware of?

The question takes me by surprise. I don’t have a quick, easy answer. Sensei is silent; he’s not offering anything. He waits. He expects an answer. I think about it. Hesitantly I start to give a response:

“I’ll tell you why I’m here. I love the zazen, the sitting that I’m doing at the Zen Center. I love the kinhin, the walking meditation. I have terrible nightmares; my therapist told me it’s from my worst memories locked in my body. And, sometimes I get so restless that I just want to—”

“Scream—” he says.

“Yes.”

“So. I see. Scream, right now.”

“What?”

“Go ahead. Scream.”

I look at Jimmy, but he’s stepped back and is letting me have this moment with Sensei on my own.

“Scream what?”

“Anything. ‘Yes!’ ‘No!’ Your scream is a meditation also.”

“I don’t know,” I say doubtfully. Okay, I’m not completely ignorant. I’ve heard of Primal Screaming. It’s so unlike anything Eli and Reva are teaching me.

“There are many ways,” Sensei says. “Even within Zen. Many ways. You have to find your own way within the No Way.”

“No Way?”

“Exactly.” And he opens his mouth and lets loose a yell that roars around the dojo until I think it’s going to shatter the windows that rim the upper level of the room.

“Try,” he says. “First, go deeply silent. Then, scream!”

“Ah,” I say. ‘Go deeply silent’ is a clue. I kneel down, make myself small, concentrate my breathing, empty my mind. I go toward the place that I’ve been seeking these months in the zendo. This time when I get there—instead of grasping to stay in it and immediately losing it, always fleeting, never settling in—this time I jump up and give out a shriek that comes from the depths of my being, from the inside of a smashed car, from the newfound power I have found through meditation. I start to cry, but then I stop.

Sensei smiles for the first time and says in a kind, almost gentle voice: “You have pain locked in your body. I’m glad you are here even if it is for a short time.”

Can he see the pain I am holding? Can he see the hot molten river that still flows somewhere inside me? The one I’ve tried and am still trying to bury. To escape. Can he see the pain from the accident? The part Sarah says is locked in me?

“Now, try running around the dojo screaming.”

“Wait, what? Why? What for?”

“To free yourself, of course. Sitting is good, standing is good, walking is good, all will get you where you want to go. You have good teachers at the Zen Center. Now try. Cut! As if you have a samurai sword in your hands, the sharpest blade imaginable.”

“Cut what?”

“Cut everything. The air, the walls, the sky. Me. Yourself. Scream!”

I have no idea what I’m doing but I try again. And again. And again. Each time, Sensei exhorts me to try harder, express myself more and more. Finally, I get frustrated and angry, and I run around the room like a crazy woman, yelling, “Yes!” and “No!” randomly, hating the teacher, hating this foolish exercise. When I stop, I’m crying. As before, I stop myself, a new thing for me. Before I can say anything, he says: “Better.” That’s all. It’s just a moment, but in that instant of complete release I see possibilities.

At the next meditation session in the zendo I mention my first Kiri-Do class experience to Reva. She knows of the Uedas and approves of the idea of me taking up another practice.

“It can only help,” she says.

I also mention my new sword practice during an early-morning session with Sarah. She also approves, using almost the same language as Reva: “Perhaps it will help.”

I make Kiri-Do a regular part of my routine and go to class weekly. I even get a gi and a basic wooden sword, bohkutoh. I notice the students treat these plain swords with utmost respect as if they were sacred objects, keeping them in their coverings except when using them, and bowing after each use. I’m never going to be a master swordsman, but the one-pointedness, the intense focus and concentration required is certainly good for taming my erratic mind. It’s deepening my zazen in ways that I can hardly understand. I learn the basic cuts, and I enjoy the way the combination of the gently strenuous yoga and the outright arduous Kiri-Do classes complement each other.

A couple of months go by. One day after yoga class, Jimmy mentions that there’s a special Kiri-Do event planned for the weekend and asks if I would like to go.

“What is it?” I ask.

“It’s called takigyo. Waterfall training. Up in Marin. My father will lead it. If you want to come, show up at the dojo on Saturday morning.” I’m noncommittal with Jimmy. The idea brings back memories of the hike up Tennessee Valley with Sajiro. I think about it and decide I shouldn’t let the past influence the future. No regrets, the Buddhist texts say.

On Saturday, Sensei takes a vanload of students up onto Mount Tam. We drive halfway up the mountain, park in a lot near Lake Lagunitas, and hike up an almost hidden path. I soon learn why the trail is avoided by most hikers. It’s steep and slippery. Water runs down it, making footing treacherous as it parallels a runoff stream, sometimes crossing it. High up on the mountain we come upon a waterfall, the rivulet spilling over a ledge more than twenty feet up, into a shallow pool. It’s a magical place, a hidden dell of wondrous natural beauty, sheltered and tranquil, the water splashing into the pool musically. Sajiro’s words about the ocean view at Tennessee Valley come to me unbidden: “This is always here.”

“Here,” Sensei says. We all take off our daypacks and the others start to change into their white gis. No one cares about modesty, so I strip down with the rest and put on my gi. Sensei stands at the edge of the pool and chants a prayer, intermittently clapping his hands. A senior student informs me that this is a supplication to the water god to keep us safe and not send anything over the fall onto us while we’re there. “It’s a Shinto thing,” he says. I shrug off this oddity and watch as Sensei enters the water first. He stands under the plunging cascade, takes the horse riding stance, and executes tsuki punches, each time emitting a shout which reverberates over the sound of the water into the surrounding silence of the forest. When he’s satisfied that the falls are safe, he leads us, one by one under the waterfall, senior students first, and leaves us there for as long as we can stand it. Before the first person goes in, he says: “In Japan the water would be much stronger than this, and much colder, but for American students this is a good first time for takigyo.”

Some people last only seconds, others revel in the pulsing crashing liquid beating down on their heads. Some simply stand there, and others perform imaginary sword movements; and no one takes their sword into the cataract even though people have brought theirs with them. When my turn comes, I’m shocked by how cold the water is, and I think that I’ll stay in for only a second or two. I find myself standing straight and still. I lift my hand up and reach up into the water that’s crashing down and cut forward with my arms. It’s the movement I did from the balcony a long time ago, when I was planning to jump and end my life, the time when I turned away from death and towards the struggle to find a way to live.

When I step out, hands reach out to assist me. I stand by the dark wet rock next to the falls and support myself with one hand. I look at my white hand against the dark shining wet black rock. The rock is me. I am the same as the rock. We have become one.

On the next Wednesday, as I enter the dojo, I’m shy for some reason. The waterfall training humbled me and at the same time ignited a fire inside me. How can standing in cold water ignite a fire? How can my white hand be the same as black rock? How can black rock be me?

Jimmy starts the class by asking us to form a circle. This time we sit in seiza position on our knees with our eyes closed. There’s an obvious space in the circle and I’m expecting Jimmy’s father to step into that space and meditate with us. Instead, a tall blond woman quietly slips into the circle, wearing the white skirt that I have learned is called a hakama. I immediately recognize her as Jimmy’s mother. She is the Sensei’s wife, and the Sensei this evening. She has curly blond hair that frames a round beautiful face. When Jimmy ends the meditation, we all bow toward her.

She steps into the circle and asks us to hold hands, to let the energy of the circle pass through us, through the left and to the right. I’m surprised at how the circle comes alive, pulsating, swaying as one. When we start the class, we again do more cutting movements. The difference is that we do them slowly as if we are cutting through a thick liquid. We end up reaching to Ten (Heaven) and slowly cutting down. This is my movement, that I’ve done instinctually. It is the movement that saved me from jumping. It is my waterfall movement. It’s wonderful to follow this strong woman. The entire class is free hand. No swords, but plenty of movement, plenty of cutting using our hands and arms, with many different partners. The end of the class is simply running and cutting with our arms for a long time. Energy comes and goes, surges and ebbs until I am in a trance of movement and meditation.

At the end, Jimmy calls us back into a circle for meditation.

“Jimmy, your mother is amazing,” I say after class. He leads me over to introduce me, and I have a sensation of surrender. I’ve found another teacher, another woman to help me find my way.

I never miss a class of Kiri-Do. My sword work becomes more assured.

Similar to my experience in the zendo, I surpass some students who have been practicing much longer than me.

“It’s not a competition,” Mrs. Ueda tells one student who is peeved that I’m progressing so rapidly. “It’s not a competition with anyone except yourself. Remember that.”

My posture changes. I notice that when I walk down the street, people are, if not truly afraid of me, then respectful. I doubt a mugger would ever pick on me, I’m projecting too formidable a presence, without doing anything martial whatsoever.

Then one day it all ends suddenly.

In class one Wednesday evening, Jimmy’s father is watching me in partner practice with another student, Paul, a guy I don’t know well. Paul is a lanky white guy, not so much muscular as lithe, stringy, flexible, and quick. We’re practicing timing and cutting techniques. We have to catch the other’s movement. Beat him or her to the punch so to speak. Sensei stops us almost immediately after we change roles. He gives me a funny look. I can’t read it. Is he going to praise or criticize me?

“Do you want to defeat and humiliate your opponent?” he asks. “Do you wish to be victorious and ego proud? No! You want to lead them into mu, emptiness. Suck them into the vacuum space where there is no ego. Can you do that?”

He gives me that look again, and this time I think I understand. It’s a test, like the first day when he made me run around the dojo forever. I stand with my eyes closed for a long while. Sensei’s eyes are on me. Paul is waiting. To do what Sensei is looking for, I must connect with Paul in some way that I haven’t yet. I must find his center, cut it open, and let it expand. I have an instantaneous momentary vision of the poster of Kuan-yin hanging on Taisha’s door in The Laundry. Unbidden, the phrase “kill him with kindness” comes into my head.

I face Paul again, look at him as deeply as I know how, really examining him, his strengths and his pains. He looks away at the last instant before we bow. Then, each time he raises up his sword, I slash across his body in the space he’s opened up. I’m shredding him with each cut. In some weird way as I’m cutting Paul, I’m revealing myself also, opening up my shell and letting inside and outside merge. I finish the round and bow deeply to Paul, who also appears to have been strongly affected by the experience. He walks away with a slightly stunned expression on his face. Sensei approaches me. He doesn’t bow, which would be totally out of character, but he cocks his head to one side and says:

“For you the sword is a step on the path. For me, it is the path. It is my life. Different paths. I’m glad ours crossed.”

I bow, holding back tears. Sensei is dismissing me. He knows I’ll never study sword long enough or hard enough to follow his path. I can’t let anything, even the practice of Kiri-Do that I enjoy so much, get in the way of my true search. We both know this is my last class. As Sensei Ueda says so wisely, I’m on my own path and must follow it.

Interested readers can go to Odeon Press to purchase the book from a variety of sources including Amazon, Barnes & Noble Booksellers, and iTunes.