Shintaido Quebec September 2019

By Dan Raddock & Mark Bannon

Last September (2019), Master Instructor Ito led, and Shintaido Quebec, hosted a Shintaido Kenjutsu Master-class followed by a weekend Shintaido open-hand workshop including examinations for Shintaido Graduate and Shintaido Kenjutsu Shodan. Here are some notes and memories to share.

The Friday Master-class training included several variations of Diamond Eight Cut (open handed, with sword), Shoden no kata, Chuden no kata for advanced students, and a mock exam.

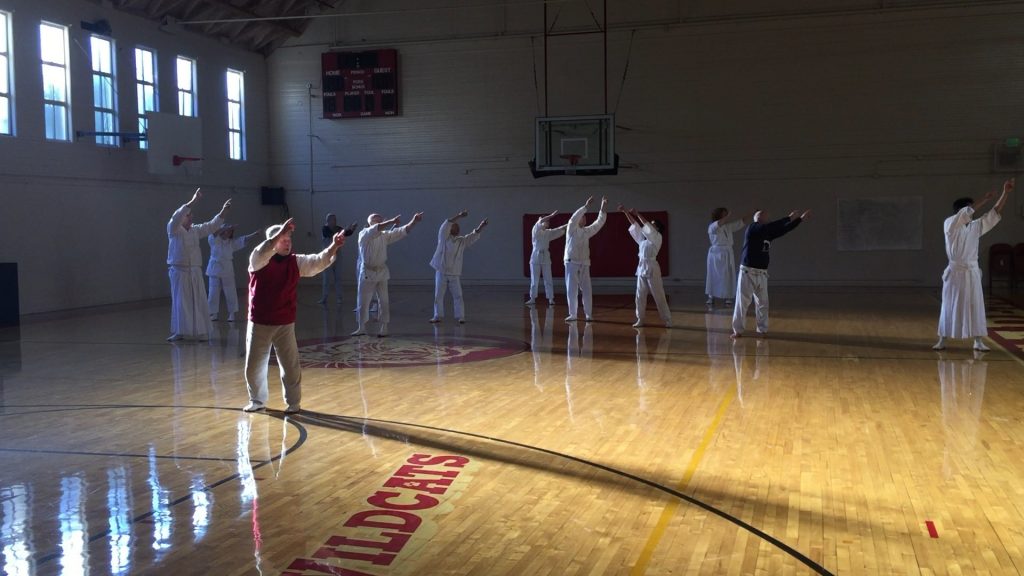

The Saturday Shintaido workshop opened with a jumbi taiso (warmup) led by Mark Bannon. The warmup was followed by a group discussion about the importance of the jo-ha-kyu structure in leading jumbi taiso and keiko itself. Jo-ha-kyu is a rhythm starting out slowly, building on itself, until crescendo. The rhythm makes it easier for the group to follow along, stay engaged, and become unified.

Later, Master Ito would again remind us of the important role and responsibility of the leader of “warm up” exercise – not just welcoming classmates and preparing them physically for the keiko, but being constantly awake to the condition of each member of the class, as well as that of the Goreisha preparing to teach. Full awareness of the environment.

Master Ito then led Eiko Dai to remind us of the importance of this fundamental practice in Shintaido generally, and more particularly, highlighting the Tenso to Shoko sequence of Eiko Dai that appears in Tenshingoso, Diamond Eight Cut, Taimyo, Kiri-oroshi Kumite, etc.

Herve’ and Mark then practiced Kiri Oroshi Kumite as mock exam in front of the group with focus on Tenso to Shoko sequence cutting movement in kiri-oroshi kumite. Special emphasis was placed on inviting your partner in, rising together to Tenso and then experiencing Shoko together – one partner taking care of the vulnerable partner experiencing the kiri-oroshi (deep cut) as the movement progressed and roles switched.

Another important theme of the workshop was Musoken, receiving the unseen attack. Master Ito introduced a series of empty-hand and then sword exercises inviting us to explore Musoken.

Staying true to the Jo-ha-kyu rhythm, we started out slowly with wakame taiso from behind. We then expanded the space with the image of someone pushing a shopping cart (two-hand tsuki) slowly towards you from behind. As crescendo, we responded to a Shintaido karate-tsuki and then sword cut/thrust from behind. Master Ito emphasized the importance of using all your sense to “feel” the attack. And, even if you are unable to react in time, always maintain (ten-chi-jin) grounded, upright posture, your awarenessand stay in the moment.

The final day of the workshop included more practice of Musoken using bokken and paired practice of sword kumite movements from shoden no kata – three jodan attacks while attacking, three gedan cuts while retreating, then switching roles to create continuous kumite. The workshop was followed by Shintaido Graduate exams for Herve’ and Mark, and Kenjutsu Shodan examinations for Dany, Bruno, Gail, Dan, and Sarah.

Three impromptu lessons/talk, by Master-instructor Ito were among the many highlights of the Quebec gathering. These spontaneous talks were full of meaning, metaphor, and history. Each of these talks explores the deeper meanings underlying Shintaido’s fundamental techniques. They reveal the roots of the techniques, as well as the spirit/way that transcends the technical.

The talks cover the following topics:

- The meaning of “dojo” and sacred space, creating a sacred space, and how these concepts relate to doing jumbi taiso at the beginning keiko

- The meaning of Musoken — perceiving the unseen – and the importance of and path to, cultivating this sensitivity

- The path between karate-do’s Odachi Zanshin (ready) stance and Tenso/Shoko; from Tsuki to Shoko; from embracing the divine to embracing humanity; and the meaning and importance of (Daijodan) Kiri Oroshi Kumite.

The weekend ended with a celebration of life in memory of Montreal Shintaidoist Anne-Marie Grandtner held in Parc Victoria on a sunny and bright Monday morning.

Special thanks also to Carole and Herve’ for their hospitality in making the Quebec workshop such a warm and welcoming event.